Particularly in this era of YouTube and Flickr, it's worth pondering what makes an image or a video clip iconic -- or "go viral," to use the social media lingo?

If the question had an easy answer, of course, Hollywood film companies and marketing and public relations firms wouldn't be throwing hundreds of millions of dollars at it.

If the question had an easy answer, of course, Hollywood film companies and marketing and public relations firms wouldn't be throwing hundreds of millions of dollars at it.

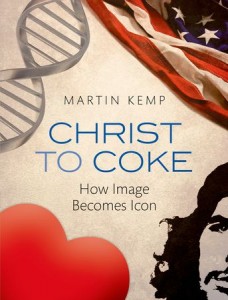

But, Martin Kemp should be commended for trying to work his way through what's at stake in an image becoming an icon in his new book, Christ to Coke: How Image Becomes Icon.

A professor emeritus of the history of art at Oxford University, Kemp tackles 11 important images and figures in his book: Christ, the cross, the heart, the lion, the Mona Lisa, Che, a Vietnam War photo of napalmed children, the American flag, Coca-Cola, DNA, and the equation E=MC?.

Kemp devotes one chapter to each of the themes, symbols, or figures, and some of the chapters reflect particularly interesting research and little-known facts. Anyone who has seen Kemp's Wikipedia page won't be surprised at his wide repertoire, but it bears reiterating. In Christ to Coke, Kemp easily navigates high art and kitsch, and complicated scientific discoveries and sociology and cultural history.

But as dazzling as Kemp's individual chapters are in their information about the first heart transplant (in South Africa, and the Jewish patient's wife worried about her husband's new gentile heart) and who really invented Coca-Cola's semi-erotic-shaped bottle, there is no overarching lesson about icons.

"There is no absolute predictability -- just a series of extraordinary stories about images that exhibit varied kinds of shared and individual characteristics," Kemp writes.

Kemp allows that though only two of his chapters address literally religious subject matter -- Christ and the cross -- the heart has a "conspicuous religious dimension." And if the definition of 'religion' is extended to "embrace devotion that accords a value to something that transcends all its apparent physical existence," he adds, "then the other eight all exhibit either religious or quasi-religious dimensions."

One wonders why Kemp abandons this approach when he seeks larger governing patterns. He calls the American flag "probably the most religious of the apparently secular images" -- as it is a "kind of sacramental object through both law and custom" -- and notes that lions can convey divine majesty, and "No one who has witnessed the elbowing crowds in front of the Mona Lisa can doubt that 'she' is the subject of cultural worship and journeys of pilgrimage."

But after arguing that it'd be tough to characterize the Coca-Cola bottle as religious "without debasing the term 'religious' to embrace such things as the worship of material consumption," Kemp dismisses religious, or quasi-religious, identity as a defining feature of icons. "We all tend to accord value to things that transcend any kind of financial and utilitarian worth," he says.

So apparently transcendence won't do as a contributing factor to icon status, though of course all successful icons are necessarily transcendent, in that they distinguish themselves from the pack of would-be icons. Perhaps identifying transcendence as a prerequisite to achieving iconic status would be a tautology, but it's actually a bit of a deep point.

A Che Guevara portrait isn't necessarily going to be successful because of it's subject matter. The photograph actually needs to be greater than the competition, just like Christ's majesty doesn't mean every crucifixion is going to be great art. Iconic themes certainly don't imply that every treatment of the themes deserve a reward. So Kemp is no doubt onto something in noticing at least some religious aspect to the icons he examines -- even the non-religious ones.

It's no wonder, then, that Kemp's first chapter on the "true icon" is arguably his most interesting one. In his treatment of Jesus' appearance, Kemp carefully traces the history of the acheiropoietos, or image not made by human hands. The sudarium (or Veronica's Veil) literally claimed iconic status by virtue of their divine creators.

Kemp doesn't suggest it, but perhaps all the 11 icons he addresses can be viewed in this light. Viewers are of course interested in Mona Lisa because they are fascinated by the image's creator, Leonardo da Vinci, and the model, Mona Lisa. But I'd argue that the painting has become iconic at least in part because it's so easy to "get lost" in the work and to forget the literal content and the creator. I'd submit that this type of transcendence might be common to all icons. The ones that have so much depth that they can hold our attention in their own right are the ones that we will cling to for many generations.

Of course this won't help us diagnose and predict which images are likely to go "viral," as it's always easier to predict the past than the future when it comes to qualitative judgments like this, but it might still be a useful template to use when we pose the very provocative question of what makes certain images become icons.

This article originally appeared in Houston Chronicle.

?

Follow Menachem Wecker on Twitter: www.twitter.com/mwecker

Source: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/menachem-wecker/only-fuzzy-factors-can-pr_b_1150011.html

bo jackson ibogaine michigan football michigan football weather houston weather houston small business saturday

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.